The small streams that come together to form the River Lymn run down from the hills west of Tetford. They pass through the village as a fast flowing stream which at this stage is the very epitome of Tennyson’s brook. Particularly just past Tetford watermill it babbles over rocks and roots as it hurries through the village but instead of carrying on east along a wide valley toward South Ormsby it takes a sharp right and enters the New England Ravine. This is because 20,000 years ago the main valley was blocked by ice. This then caused it to flood and the river to spill over a low ridge into the valley to the south and with the force of the meltwater from the glacier it cut a steep sided valley through the sandstone ridge down to the clay below. Beyond the ridge, this surge of water also gouged out a trench 500 metres wide in the soft clay all the way to Stockwith Mill before spilling out into another temporary glacial lake partly surrounding today’s village of Sausthorpe. This new course, which the river still occupies, is partly responsible for forming the prominent “knolls” that Tennyson refers to in his most acclaimed poem In Memoriam AHH. These, as described in his poem, are visible from the garden of the old rectory where he was born and lived for most of the first twenty eight years of his life. (See Tennyson’s Knolls post.)

The erosive force of the meltwater charged river made the valley bottom ten metres lower than its preglacial eastern course. Although conversely the Upper Lymndale valley bottom (See Upper Lymndale post.) was raised slightly through the deposition of sediment during the last glacial maximum when all these events took place and explains why the Lymn did not revert back to its original course in post glacial times.

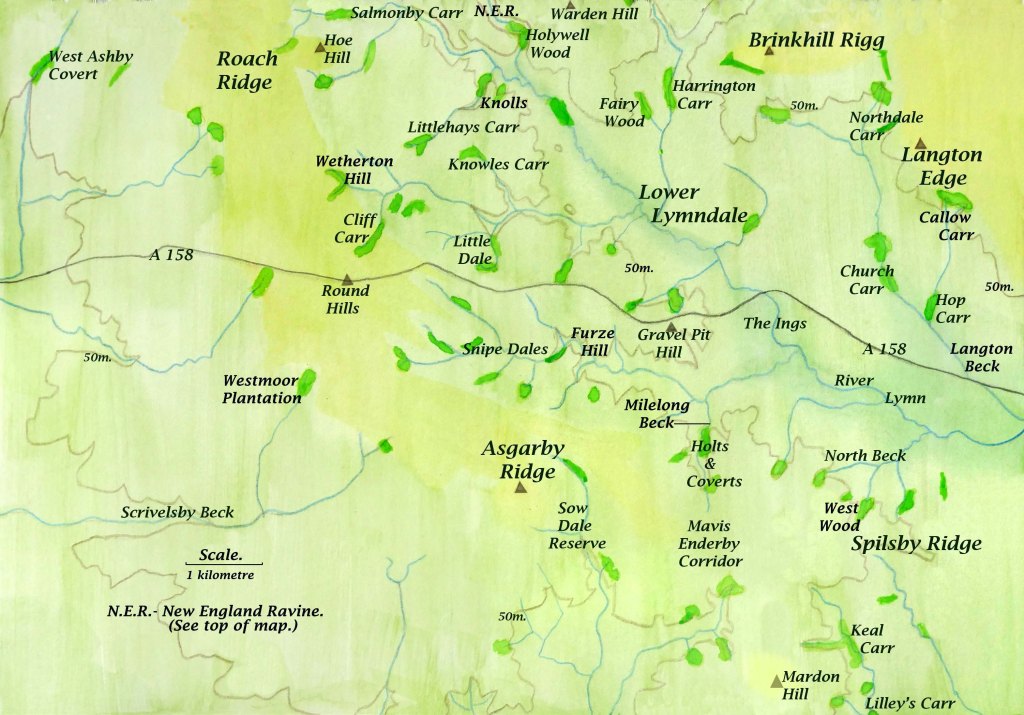

A wider reaching consequence of these events is that the lowering of the River Lymn’s profile has also allowed its many tributaries to cut down through the sandstone plateau on both sides of the river so that they all have valley floors that are wet and normally only suitable for pasture, meadow or wet woodland known locally as carrs. The first of these many tributary streams is Salmonby Beck which joins the River Lymn west of Somersby soon after it emerges from the New England Ravine. As it is higher than other streams its carr though long is narrow, as the upper part of the beck only just cuts through the sandstone, but lower tributaries of the River Lymn have generally wider valleys with many of their tributary streams occupying Carr Dales.

The point where the River Lymn and Salmonby Beck join is overlooked by Warden Hill. Over a distance of just one kilometre and a descent of seventy metres from its top down to the River Lymn several bands of strata come to the surface covering 50 million years in time from the rare Cretaceous Red Chalk capping Warden Hill to the much older but softer Kimmeridge Clay laid down during the Jurassic period. Each rock type has different properties offering opportunities for a mix of habitats although the most pronounced of these is the difference between the dry sandstone plateau on which Somersby stands and the damp clay valley bottom of the River Lymn which curves around the village though ten metres below it. The many strata of rock surrounding Lymndale are dealt with in more detail in the previous post dealing with the geology of the area (Distribution and Geology of Carr Dales.). In this post, however, I will describe how the dry porous sandstone overlying impervious damp heavy clay is responsible for creating most of the Carr Dales in the Wolds that can act as important wildlife corridors.

In between Salmonby Carr in the north and Keal Carr close to the Fens and probably the finest surviving example of the alder carrs of the southern Wolds, there are a score or more of other similar wet wooded valleys many of which are hidden and have no access but provide important habitat and refuge for wildlife. This archipelago of wildwood islands need to be connected by corridors along the streams that flow through them to create a dendritic network of links for wildlife crisscrossing Lymndale.

Snipe Dales is one of the few semi-natural wet valley systems still surviving in Lincolnshire where many streams gather to flow east past the southern flank of Gravel Pit Hill and is the most central, accessible and best protected of all these valleys with much of its length made up of a country park and two Lincolnshire Wildlife Trust ( LWT) nature reserves. (See Beyond Snipe Dales post.)This has allowed the course of the stream to flow through a natural riverine corridor. There are other shorter streams that remain largely undisturbed as in Little Dale to the north, just over the ridge that carries the A 158, which has access but as yet no protection. Some of the holts and coverts north of Mavis Enderby from which the waters of Milelong Beck emerge are SSSIs (Sites of Special Scientific Interest) but are not accessible. This beck joins the waters from Snipe Dales Beck flowing east to then ultimately merge with those of the Lymn, which by this time has grown to become a river set in its own floodplain.

The sad thing though is that Snipe Dales Beck, which for Lincolnshire carries relatively pure water, over the last few hundred metres of its course gets diverted into a straight roadside ditch. Whereas just a hundred years ago it meandered gracefully across a wet meadow before joining the Lymn. Its natural course can still be traced on the local 1 to 25,000 OS map as the dotted line of the parish boundary. This interference with the natural flow of the water continues once it has joined the river which today is restrained by embankments from overflowing onto its natural floodplain. Downstream from the A 158 this floodplain was once a large area of meadows for summer grazing and haymaking when it would have been full of wildflowers. The area is still called The Ings which is an old name for meadows. In Lincolnshire by far the biggest loss of habitat across the county is permanent pasture and meadows in particular. It is thought that today there is just 142 hectares of meadow left in the whole of Lincolnshire (Lincolnshire Wildlife Trust 2000). Yet we know that just Lymndale alone at the time of the DB had roughly this much meadow.

Returning to the SSSIs near Mavis Enderby the headstream of this valley begins close to the prominent church of this sleepy little village and is the most southerly of all the River Lymn’s main feeder streams. The village is a cul de sac lying just off the B 1195, a fast road connecting Spilsby and Horncastle. Despite passing the village, where there is a roadside footpath and a crossroads just beyond, there is surprisingly no speed restriction in force along this section of the road.

From the point of view of wildlife, this is also the narrowest point of an extension of Asgarby Ridge that separates the catchment area of the River Lymn from the valleys and streams that converge on Old Bolingbroke including Sow Dale, which is a LWT nature reserve for much of its length. This means that the section of road between Mavis Enderby and the crossroads crosses a natural corridor between two important wildlife habitats which occupy the steep narrow valleys on either side of this fast road. This also is a good reason for slowing down traffic along this section. A similar set of circumstances could also be argued for speed restrictions a few miles to the north across the Lymn Valley along the section of the A 16 where it passes through Dalby.

The A 158, as seen clearly on the map, cuts the Carr Dales in two so is a far greater problem. It also in part marks the southern edge of the Lincolnshire Wolds AONB, and has allowed the village of Hagworthingham, which straddles the road, to grow substantially in recent years. The development of this busy coast road is relatively recent as its destination, the seaside town of Skegness, had a population of less than 500 until the railway arrived in 1873. Now nearly all visitors arrive by car and during the summer months, the still fairly small town transforms into a city by the sea extending twelve kilometres along the coast as far as Chapel St. Leonard’s with most of the accommodation in the form of caravan parks.

The great majority of visitors head for the coast along A 158 which has a 40mph speed restriction through Hagworthingham but this needs to be extended east as far as the River Lymn to give wildlife a chance to cross it. Building a visitor centre along this stretch of road on its north side at Cinder Hill would allow people a convenient and scenic spot to break their long journey. This location offers panoramic views across Tennyson Country allowing those who might otherwise just pass through to appreciate the significance of the area both historically and geologically with views extending right across Lower Lymndale to the bold line of the chalk escarpment dominating the northern skyline.

Cinder Hill overlooks the River Lymn on its north and east sides and along the river are the sites of two watermills. About a kilometre upstream is Stockwith Mill and a little further away than this downstream is Aswardby Mill. Stockwith Mill claims to have strong associations with Tennyson because just beyond the mill was the Reverend George Clayton Tennyson, Alfred’s father, parish of the twin villages of Somersby and Bag Enderby nestled under Warden Hill. This said the description of the mill in The Miller’s Daughter tends to resemble Tetford Mill more and is closer to Alfred’s home of the rectory in Somersby. This and the fact that Alfred for a time was a regular visitor to Harrington seeking the attention of Rosemary Baring shows how much of Lymndale was familiar to the young poet.

Aswardby Mill, though less accessible as it is well set back from any road, has a long complex history. Just the fact that it is located at the junction of three parishes and close to a fourth is an indication of its historic importance as the last mill before the river slows to meander across a widening flood plain. Curiously the mill is nearest to Sausthorpe with Aswardby parish only connected to the mill by a long narrow southern extension of its parish boundary along the river. Although now the smallest and quietest of the villages that surround the watermill from evidence gleaned from aerial photographs of crop marks it is thought that in Roman times Aswardby or the then settlement close to it was the largest in Lymndale which was generally heavily settled at this time. Even when the Domesday Book was compiled Lymndale was still heavily populated and judging by the village names, nearly all ending in by, they were mainly Danes. Surprisingly neither Aswardby nor Sausthorpe are included in the book. (See The Mystery of the Missing Parishes post.) All this tends to lead to the conclusion that Aswardby Mill probably has Roman origins.

From just this brief excursion through time it is clear that the view extending across Lymndale from Cinder Hill, although always basically rural, has changed constantly over time while today continuing to be rural and still fortunately undeveloped. In a following post I will be exploring the possibility that just to the south of the A 158 the potential for all of the Snipe Dales Beck catchment becoming a protected area and money being available to reinstate the River Lymn back to its natural meandering course across its floodplain (See – A different way to managing the land post.). If all this were possible then Lower Lymndale could finally achieve the status and recognition it deserves.